On Twitter, people want to follow personal versus official accounts of journalists

20TH DECEMBER 2011 by NANCY MESSIEH

The International Journal of Communication has released a report, looking back on how Twitter was used this year to disseminate information during the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia.

The study looks at where the information was coming from – whether activists, bloggers, journalists or from mainstream media – and analysing the reach of each of these roles, as well as how ”Twitter plays a “key role in amplifying and spreading timely information across the globe.”

Analysing over 150,000 tweets posted from January 12 to 19, 2011 using the hashtags #sidibouzid’ or ‘tunisia’ and over 200,00 tweets posted from January 24 to 29, 2011, containing the hashtags ‘#egypt’ or ‘#jan25,′ a huge wealth of information on how content on Twitter is being received, depending on who’s doing the tweeting.

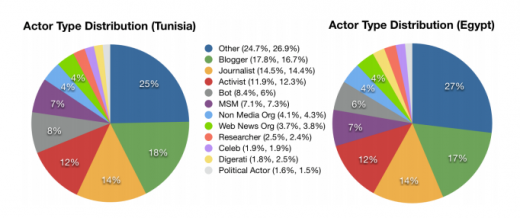

In both Egypt and Tunisia, bloggers, journalists and activists were the most prominent in disseminating information, accounting together for 43% of the accounts tweeting about Egypt and 44% tweeting about Tunisia, versus just 7% representing mainstream media accounts in each of the countries.

This sheds an interesting light on how Twitter is being used in journalism . While all major mainstream media outlets have a strong presence on Twitter, some with millions of followers, when it comes to how information spreads through Twitter – when it’s coming from personal, individual accounts, it is likely to reach a larger audience.

In the case of both Tunisia and Egypt, it is possible that having journalists on the ground, reporting directly from their Twitter accounts made for more immediate impressions. While any journalist probably has to be cautious about what they say on Twitter, the immediacy of reaching their readers through tweets, in the heat of the moment, is far more honest.

Over all, in both Egypt and Tunisia, 70% of the accounts tweeting news belonged to individuals, versus 30% belonging to organizations, despite the fact that organizations tweet more often and have more followers.

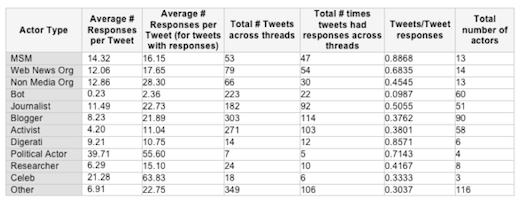

The extent of interaction can be seen in the average number of responses a tweet gets, depending on their particular role. Mainstream media accounts get, on average, 16 tweets in response. The types of Twitter accounts that get the most responses are celebrities, with an average of 63, followed by political actors at 55.

Mainstream media only beats out researchers, activists and bots. Journalists get an average of 22 responses. This can probably be put down to the fact that users are more likely to respond to an account, when they know there’s even the slighted possibility of getting a reply.

The study gives a specific example of how mainstream media tweets are picked up by other users:

On January 15, 2011, @guardiannews (official Guardian account) posts “Tunisia gets third leader in 24 hours http://gu.com/p/2mev2/tf” with a link to an article from its Tunisia coverage. Within a few hours, a number of journalists (@acarvin, @monaeltahawy, @Brian_Whit, @mfatta7) and activists (@Sonja_jo, @exiledsurfer) repost the article; this generates a number of retweets. This is representative of a typical MSM information flow, where there is little to no interaction with their audience.

In comparison, individual journalists are likely to retweet one another, ensuring that the tweet reaches a far wider audience:

On January 25, 2011, @adamakary (Adam Makary), an Al Jazeera producer, writes: “Police guard in tahrir tells me, I’m just following orders, doing my job. Otherwise, I’d be with the protesters #jan25 #egypt.” Within a minute, @evanchill (Evan Hill), another Al Jazeera producer, retweets Adam’s original post. Within 10 minutes, it is retweeted by @exiledsurfer (activist) and @ashrafkhalil (journalist). After a few hours, it reaches @octavianasr (journalist), and is then retweeted widely again (see spike on right side of graph in Figure 5). This is an example of an information flow that started with a journalist and was heavily picked up by other journalists.

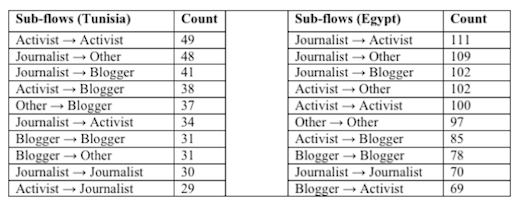

The study reveals how these different roles interact with one another. Twitter has the dangerous potential to become nothing more than one big rumour mill, and so more often than not, individual types of groups tend to retweet or follow each other.

Looking at what they identify as ‘sub-flow’ in the study, you can see that activists are more likely to retweet one another in Tunisia, while in Egypt, journalists retweet activists and bloggers the most.

The study reads:

In both datasets, journalists and activists serve primarily as key information sources, while bloggers and activists are more likely to retweet content and, thus, serve as key information routers. While there are substantially more journalists actively posting and reposting content about Egypt, the general retweet behavior between the two datasets is similar. In both datasets, journalist content tends to be re-posted frequently by bloggers, activists, and other journalists.

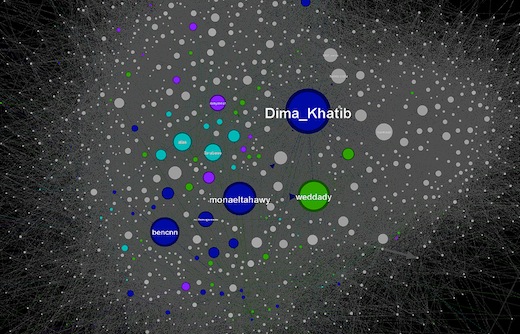

The data from the study was also used to create some pretty interesting visualizations posted on Global Voices, showing how tweeps influence each other, and who does most of the influencing.

The visualizations are fascinating because they show not only who are the most influential tweeps when it comes to the topic of the Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings, but also shows the extent of the network they are influencing.

Individual journalists stand out, with Dima Khatib, Mona El Tahawy and CNN’s Benn Wedeman among the first names you spot, followed by prominent Mauritanian activist, and Global Voices writer Nasser Wedaddy, who is just as prominent.

In order to visualize mainstream media’s influence, you have to zoom much further in to the network in order to catch a glimpse of their accounts, reinforcing the idea that people on Twitter prefer to get their news from real people, as opposed to social media accounts run by anonymous employees.

The full report is available in PDF format here.

No comments:

Post a Comment